words by DOM THOMAS

Concept

When we began thinking about Fairlight, a steel road bike was the first bike on the list. Not a race bike but an audax/all day/all season bike (or whatever the latest name is!) that could be ridden 12 months of the year and would be equally capable on a daily commute, a fast 2 hour blast with some friends, or a week of touring. It is the type of bike that I have ridden most over the last 5 years and it really is a ‘go to’ bike for any riding on tarmac.

I don’t like the term ‘classic steel road bike’ because to me it seems to infer ‘retro’ or a bike stuck in the past, the Strael definitely isn’t that. I believe that it is important to always give consideration to what is tried and tested, but at the same time new designs should be relevant and contemporary. The bike industry has been going full charge over the last few years and the line between ‘ genuine functional improvement’ and ‘new standard just to sell more bikes’ is a very thin one. I can assure you I pay full attention to all the new standards but ultimately I design bikes to be as functional as possible. Functional from a quality of ride perspective but also making the bike as useful and practical as possible.

Ultimately I wanted to make a bike that had the handling and stiffness of a race bike with the comfort and versatility of an audax bike. I’ve tried to explain most of my design decisions below.

All Season Riding

What does All Season mean? It simply means that the bike can be ridden all year round, on a variety of tarmacked surfaces and you should be able to fit proper full length mudguards when required. The recent trend towards bigger tyres and lower pressure is a good thing, so we wanted the Strael to comfortably be able to run 32c rubber or 28/30c (depending on the tyre brand) with guards. With mudguards and bigger tyres we also wanted to be able to fit a rear rack for light touring duty.

So how do bigger tyres and mudguard capacity affect geometry? Well you need to lengthen the chainstays and likewise the fork is usually a bit longer. A race bike has a chainstay length of approximately 410mm length, for the Strael we settled upon 418mm which gives sufficient seat tube/tyre clearance when using 32’s but is as short as possible (without bending or offsetting the seat tube) to give a snappy race like feel.

Likewise with the fork we wanted to ensure clearance but keep it as short as possible and still very much a road fork. I’ve seen so many brands resort to offering carbon cyclocross forks (approx. 400mm axle to crown) on all season road bikes to ensure clearances but such a long fork messes up the geometry on smaller sizes and is a bit of a cop out in my opinon. We designed and made our own fork for Strael, which has an axle to crown length of 381mm. With a 32c treaded tyre fitted there is LOADS of clearance. We designed the fork to have proper mudguard eyelets on the dropouts so that the mudguard stays don’t need to be bent for fitting. We also wanted to have a dynamo lamp mount on the fork for self-sufficient winter riding and trans continental style endurance racing.

The other geometry consideration once you add bigger tyres and mudguards is ‘front-center’, which is the distance between the bottom bracket and the front hub. We carefully balanced seat angle, head angle and top tube length to give what we feel is the best compromise between fast handling and acceptable clearances.

Disc brakes are currently the most talked about subject in road bike design. Do I need them? Are they a fad? As I see it the real benefit of disc brakes is that they work predictably and reliably in ALL weather conditions. For an ‘all season road’ bike that reason alone is enough to include them in the design. Shimano introduced the ‘flat mount’ standard a couple of years ago, which is a disc caliper specific for road bikes. The caliper is smaller, tidier and designed to fit within the rear triangle. It is clear that the main drive behind this design was for tidier integration into the chainstays of carbon road bikes. For steel bike designers/builders it caused a bit of a headache with the need to design completely new dropouts etc. On the Strael I opted to use an investment cast dropout design, which means that production is a little easier as the disc mount is already fully integrated into the finished dropout. This method requires no post weld machining of the chainstays to fit the brake mounts which also means that we can use a thinner walled chain stay (0.6mm). The other benefit is that a time saving in the factory means a cost saving for the customer.

The other big subject that goes hand in hand with disc brakes is thru axles. The idea behind thru axles is that they reduce flex and rotor rubbing, although I do not for one minute believe that to be an issue on all road disc frames. After significant testing of the Strael we knew that flex and rotor rub wasn’t an issue that we needed to be concerned with, especially with the stiffness of the cast dropouts. Nevertheless, we proceeded with samples of a thru axle version of the dropout but ultimately the design only added unwanted grams to a frame where we had worked so hard to keep weight at a minimum.

It was important to me that the frame was easily serviceable and with a minimum of fuss. With this in mind one of the things we ruled out was internal cable routing. It is so often a source of rattling and usually a pain to replace cables. Sure, it gives a clean aesthetic but I would always prioritize ease of maintenance over any visual benefits, especially on a bike that is going be ridden hard all year round.

Tubing selection and design

I set a goal of achieving 1.9Kg for a 56cm frame, which as far as I could tell would make it the lightest production steel disc road frame on the market. ‘Production’ being the key word because this frame would have to be ISO fatigue tested which means the frame is subjected to impact tests, as well as horizontal, vertical and pedal force simulations at 10,000 cycles each! I could build a 1500g steel frame tomorrow but it wouldn’t get anywhere close to passing these stringent tests.

For every bike that I design, the tubes are always picked individually based on the forces acting upon them and the desired stiffness, compliance and/or clearance required. The Strael is the sum of all the lessons I have learnt over the years and represents the very best all season steel road bike I can design. Early on in the project I contacted my friends at Reynolds steel, as I would need their assistance in getting the tubes designed and manufactured to my required specs. As always they were only too happy to help.

The main triangle (top tube, downtube, seat tube) of the Strael is all Reynolds 853, which with the exception of stainless 953, is their flagship steel and offers the best compromise between performance and value. There seems to be a trend of late on high-end steel frames to use great big oversized down tubes (mimicking carbon bike aesthetics) but in my opinion this just numbs the ride and you are then more reliant on bigger tyres and comfortable well-built wheels. The downtube on the Strael is a 34.9mm bi oval tube, which means it is ovalised to 30x40mm at the ends but in opposite planes to each other. This is a tube I have used in the past and I love the way it rides; stiff in the right places while still maintaining the compliance you expect. The 40mm horizontal oval at the BB adds lateral stiffness, where as the vertical oval at the headtube gives the strongest weld at the most highly stressed area of the frame. Rather than using the stock 853 offering I asked Reynolds if they could make a lighter version, they duly obliged and produced an 853 Pro Team version, butted to 0.7/0.5/0.7mm.

The top tube is a 25.4mm tube that has been mechanically ovalised as much as possible; the result is a full 20x30mm oval tube. The stiffness in the horizontal plain of a 30mm tube to counteract side to side loading forces, while the narrow 20mm tube in the vertical plain means it provides superb comfort. We were able to save some further weight here by using a 0.7/0.4/0.7mm butt.

The fashion over the years has been for oval chainstays (e.g. 17x27mm oval), the reason for this is that they give lots of tyre clearance and they are relatively easy to build with because they require less bending and dimpling. Also aesthetically they look purposeful because side on they look big and give the perception of stiffness. The reality is that they are big and stiff in the wrong way. What I mean is that the main forces acting upon the chainstays (and which the chainstays should therefore be resisting) are side-to-side (horizontal) pedaling forces from the rider. Ideally you want the chainstay to be wide in the horizontal direction (to resist pedaling) and narrow in the vertical direction (to help comfort), oval stays are opposite to this! So on the Strael we use Reynolds 631 22mm round chainstays. Versus a 27×17 oval they are 5mm wider (22-17 = 5) and 5mm narrower (27-22= 5), so exactly what you want! Stiffer but more comfortable. We dimple and gently curve the chainstays to give sufficient clearance for a 32c tyre while maintaining a 418mm chainstay length. We chose to use Reynolds 631 instead of 853 for the chainstays because 631 is not heat-treated and therefore slightly easier to dimples and shape. We don’t gain any weight versus a heat treated version as the butt thickness offered by Reynolds is the same for both, in this case a 0.8/0.6mm butt.

With the same theory of a rounder tube tube being better for the job, we also prototyped the frame with 19mm chain stays. Comfort was very similar for both frames so we decided to take the additional pedalling stiffness that the larger 22mm stay would offer, it’s difficult to feel such marginal differences but the maths doesn’t lie. On tough out of the saddle climbs the extra 6 mm of contact area ((22-19) x 2) at the BB will make a difference and help to accelerate you forwards.

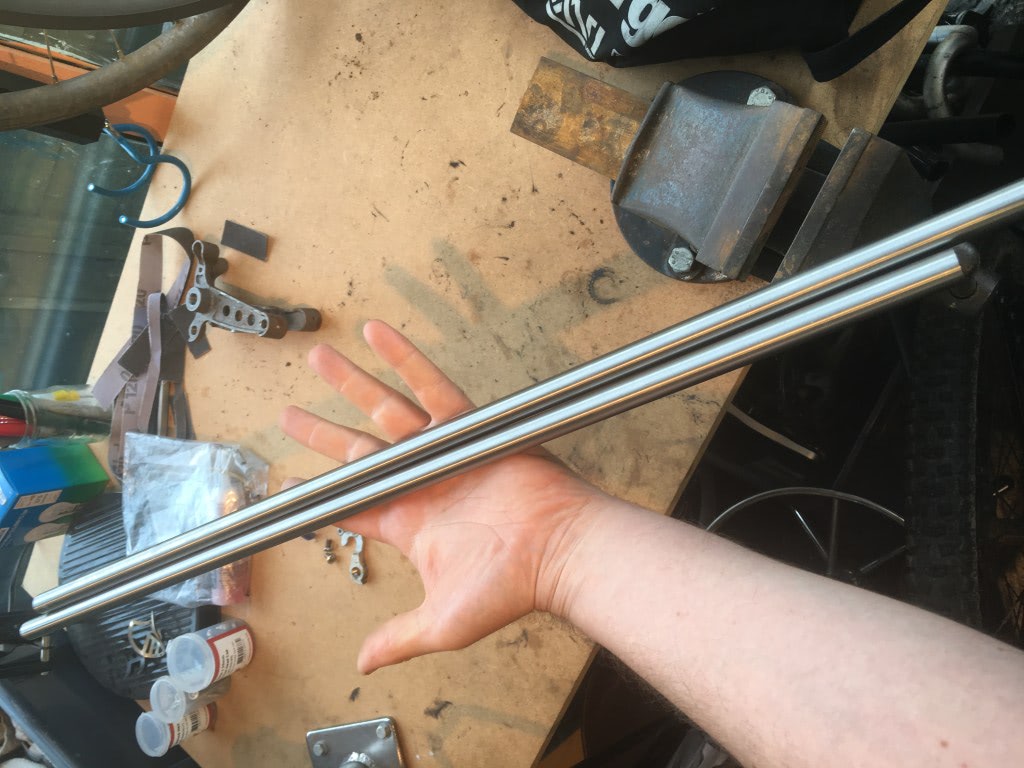

Seat stays finish the rear triangle and for these I wanted to save some weight. Most steel road frames use a 16mm seat stay that taper down to approximately 11-12mm by the time it reaches the dropout to make for easier joining. As we are using a cowled dropout we didn’t need the tapered section so I wanted to use a constant diameter tube. As there is plenty of horizontal stiffness in the chainstays I knew we could go down to a 14mm tube without sacrificing the racy feel of the back end. By heat-treating the tube for extra strength we could have a very thin wall thickness of 0.6mm throughout the length of the stay versus a non heat-treated version. We settled upon heat-treated Reynolds 725 14mm non-tapered 0.6mm tubes.

The bottom bracket is a standard 68mm threaded BB, by far the most reliable solution. Various press fit designs have entered the market over the last few years and in the large part this is to do with the evolution of carbon frames. The larger physical size of the material/tubes versus steel means that real estate in the bb area is often tight so press fit helps increase space. On the Strael the combination of the 40mm wide down tube and the 22.2mm round chainstays means there is ample BB stiffness without resorting to a press fit solution or indeed to a larger threaded shell such as the new T47 standard.

The Strael is without doubt the best road bike I have designed, it is fast and efficient yet wonderfully comfortable for long days in the saddle. Every element of the design has been considered and the finished product is testament to that.

You must be logged in to post a comment.